By: Rachel McDonough

Case File: 53475/352

Immigrant: Margarethe Schenk

On August 7, 1912, a “pale, frightened looking girl” named Margarethe Schenk stepped off the S.S. Campanello and onto the shores of Ellis Island. Arriving from Elstein, Germany with only two dollars to her name and unaccompanied by a parent at the tender age of fifteen, immigration inspectors saw her as “Likely to become a Public Charge”. She told inspectors that she was going to live with her aunt and uncle, a Dr. Paul Von Erden and his wife, Mary. Mary Von Erden claimed to be a second cousin to Schenk’s mother, rather than her sister, but this was not a strong enough family tie to make her legally obligated to care for Schenk. They also claimed they would send their “niece” to school and have her take up a trade later with a relative of theirs.

Dr. Von Erden claimed he was a veterinarian with an office in Hoboken, New Jersey, while his wife claimed that he did not have an office. This initial discrepancy gave the inspectors cause for suspicion, and their suspicion grew even greater when it was revealed that the Von Erdens had helped transport three girls, including Schenk, to America to work for them. This went against Mrs. Von Erden’s initial testimony that she was merely bringing her “niece” with her on the way back to the United States after visiting family in her native Germany. It seemed Mrs. Von Erden had other motives beyond her initial testimony claiming that she took Schenk with her simply because “she wanted to come to America.”

The other two girls who came with Mrs. Von Erden were ultimately refused employment by the Von Erdens because they could not pay back the cost of their passage in full, and both found relatives to stay with in New York. Only Schenk remained with Von Erden. Her parents, upon not hearing word back from their daughter once she arrived, requested her return. The Burgomeister of Elstein, a government official in Schenk’s hometown, was notified of the issue and wrote to officials at Ellis Island stating that while it “could not be claimed that Margarethe Schenk was abducted,” nevertheless there was some concern about her whereabouts.

Once it became clear that the Von Erdens would provide for her, Schenk was released from Ellis Island and allowed to stay with them. While initially a school bond was required, it was later dropped seeing as Schenk was nearly old enough for it to be no longer be mandated and would have employment with the Von Erdens. However, the case did not end there. A little over a month later, Inspector Helen Bullis was sent to their home with the task of investigating how the Von Erdens were treating their “niece.”

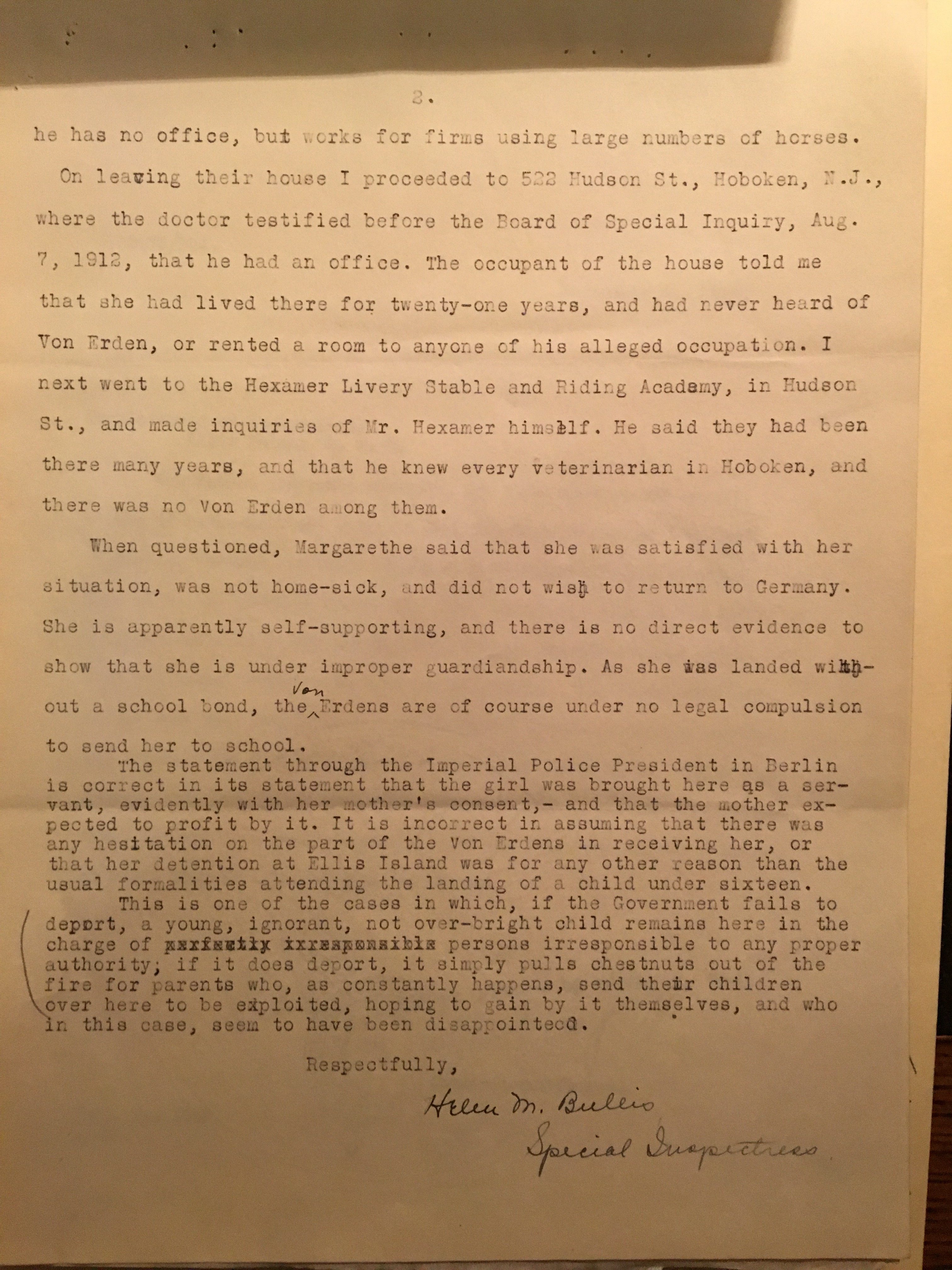

In the early twentieth century, there was a great fear of white slavery and the trafficking of women for purposes of prostitution, so extra care had to be taken to ensure that Margarethe Schenk was not being brought to the United States for nefarious purposes. This moved the cause for investigation into her case from the initial suspicion that she might become a public charge to the area of moral turpitude. It was feared that young Schenk had fallen victim to sex trafficking. When Bullis went to the address that supposedly held Dr. Von Erden’s office, she found that no one in the area knew of any veterinarian by that name. It became clear that the Von Erdens were lying about more than just their initial intentions for their “niece.” Yet, despite this, Schenk was still allowed to stay with the Von Erdens as a hired nurse girl once it was clear that she was being paid and was not being used for any nefarious purposes. After this final investigation, the case was closed and Margarethe Schenk’s ultimate fate and relation to her benefactors remains a mystery.

Document Analysis

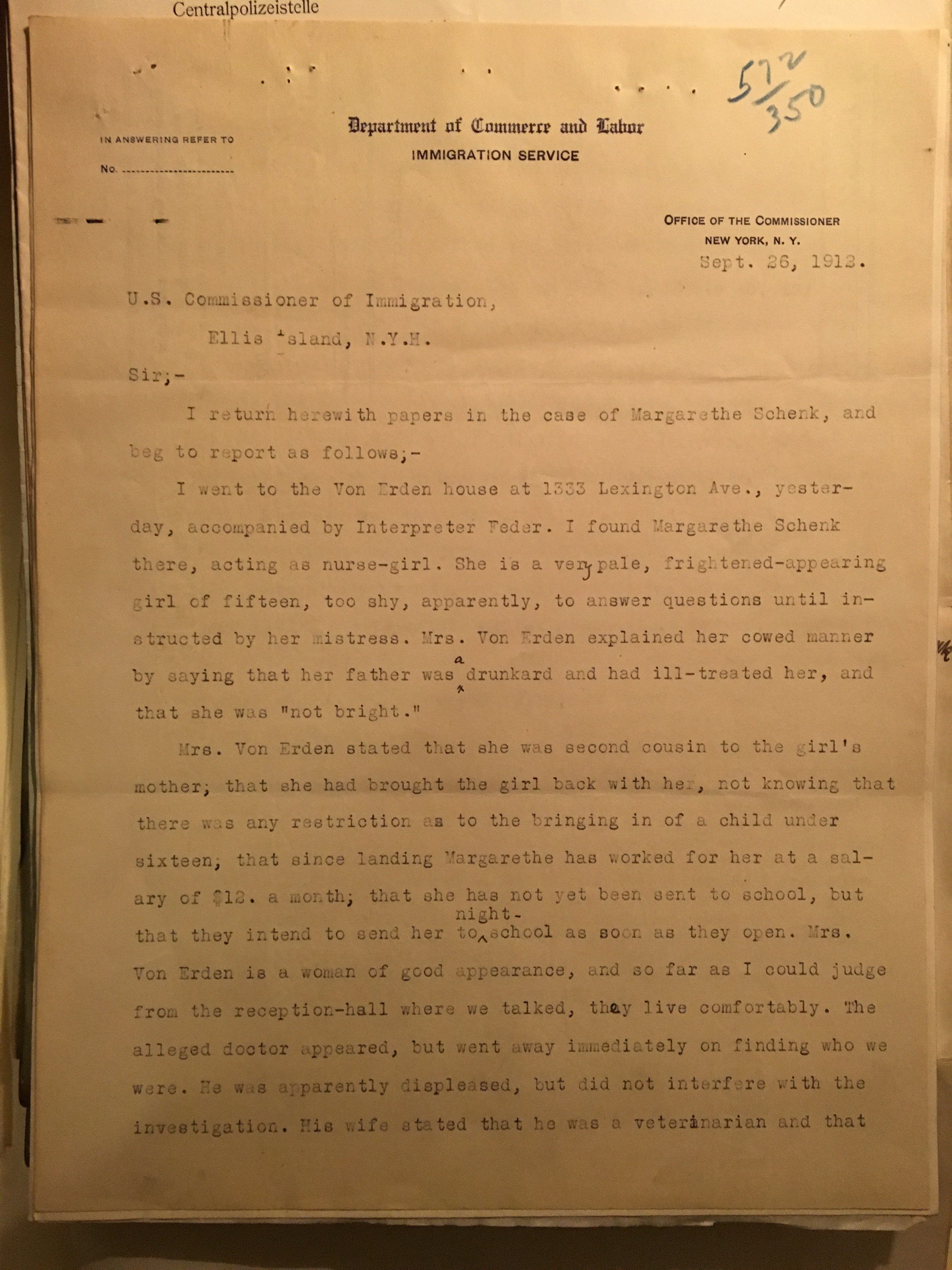

This letter is addressed to the United States Commissioner of Immigration for Ellis Island from Special Inspector Helen Bullis. It may be surprising to note that, in 1912, the inspector was a woman. The emergence of women in investigations and social work in the Victorian era was largely thanks to pioneering women in the field like the famous “Petticoat Inspectors” — women who went undercover among boarding teams to catch any potential sex traffickers of women or girls, as well as to ensure the safety of women traveling alone.

In the letter, Inspector Bullis details the events of her most recent investigation as to the identity and intentions of the Von Erdens, the supposed relatives that Schenk would be living with. Dr. Von Erden was immediately suspicious of the inspector, and Inspector Bullis found Schenk to be reluctant to answer questions. Mrs. Von Erden attributed this to previous abuse in Germany and to Schenk being “not very bright.”

Bullis’s intentions were twofold: to find out if Schenk was likely to become a

public charge due to her lack of legally liable relatives, and to find out if she was being trafficked. Despite her discovery that Dr. Von Erden had lied about his profession and the Von Erdens’ intent on keeping Schenk as a domestic servant, Bullis allowed her to stay, as she saw no evidence of her being required to do any kind of sex work.

Why It Matters

Margarethe Schenk’s case is of both historical and contemporary importance. It provides insight into the sociopolitical climate of two countries in the pre-World War One Era. It gives us a tiny glimpse into the German Empire just two years before its fall, as well as the world of New York City in the late Victorian Era. With Inspector Helen Bullis, we see the rise of female social workers in this time period. It also, most importantly, shows us the attitudes the United States government had toward immigrants based on race and gender. A young white woman with little money on her person was regarded as a potential burden to society rather than a threat, and there was a lot more concern for her welfare when the potential for white slavery was involved — a kindness rarely shown to men and immigrants of color.

While the term “white slavery” is now considered incredibly outdated, human trafficking is still a significant problem all over the world — especially the trafficking of immigrant women and children. Both the United States and German governments took steps to ensure that Margarethe Schenk was not being trafficked, though they seemed to lose interest in her welfare once it became clear that she was not required to do anything sexual, despite her guardians having lied about their identities. Today, immigrant children are often kept in detention without sponsorship or legal representation for years. It makes one wonder how far exactly the country has progressed since the case of Margarethe Schenk.

Further Questions

1) From what Inspector Bullis reported, the Von Erdens may not have had Margarethe Schenk’s best interests at heart when taking her in. Do you think allowing Schenk to stay with them was the right decision?

2) Is it the state’s responsibility to ensure a child immigrant’s guardians have their best interests in mind even if the child is not in any immediate danger?

3) How did Margarethe Schenk’s race, gender, age, and nationality factor into whether or not she was allowed to stay in the United States?