By: Barbara Shi

Case File: 53632/55

Immigrant: Antonio Baez

Antonio Baez’s journey in America began in January of 1913, after he discreetly disembarked the S.S. Montevideo at the port of New York without undergoing mandatory inspections. Though he initially claimed to have worked on the boat, he later revealed that a Spanish-speaking passenger helped him board without having his information recorded, making him a stowaway. Baez even managed to board a second vessel, a Mallory Line steamer, from New York to Mobile, Alabama, soon after leaving the S.S. Montevideo. His reasons for travelling south may have been due to his claims about having a cousin in New Orleans, though he remained in Alabama for months with no attempts to contact his alleged relative. Baez eventually proceeded “to break in some houses around Monroeville [in Monroe county]…and in [Conecuh] county,” leading to his conviction in late April, where he was sent to work in a turpentine camp.

Baez became part of a system called convict leasing, where prisons would lease convicts to private institutions, such as turpentine camps, to lower prison maintenance costs and profit from prisoners’ labor. These camps notoriously consisted of intense and grueling labor that was publicly denounced by newspapers, who described it as, “difficult, dirty, physically exhausting, and often dangerous.” After months of laboring in sweltering heat, Baez attempted to escape the camp, only to be shot in the leg by a guard and transferred to a separate prison. These harsh conditions likely triggered Baez’s desire for freedom and may have ultimately sparked his willingness to return to Argentina. However, his wound would create numerous complications that eventually led to major delays in his return.

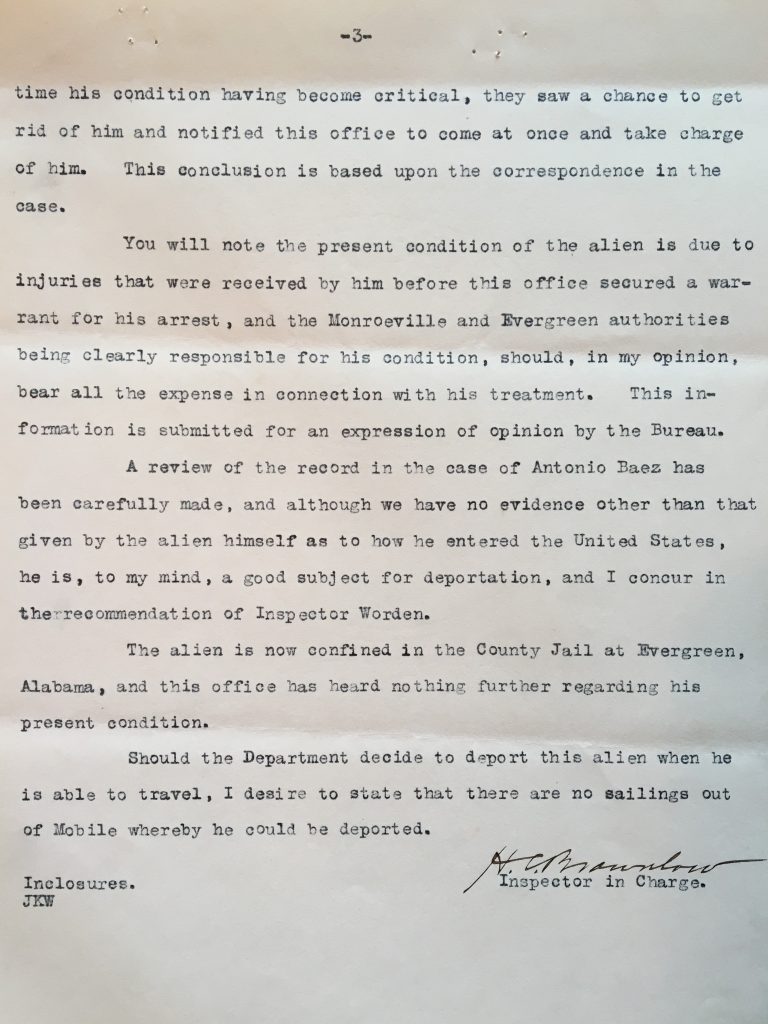

Baez’s injury uncovered a strained relationship between local and federal law enforcement, which was evident in communications between officials from both levels. Inspector-in-Charge Brownlow, who worked for the Bureau of Immigration, alerted the federal government about his suspicions that local law enforcement “saw a chance to get rid of [Baez]” following Baez’s injury, and only then did they “notify [the inspector’s office] to come at once and take charge of him.” The inspectors concluded that the Monroeville sheriff had originally reported Baez for his unlawful entry, but only pushed for his deportation after he was no longer useful for labor. This sheriff also failed to report Baez’s injury, and it was only disclosed to federal authorities by another sheriff after Baez was transferred to a different prison. After this discovery, the federal government chose to immediately cancel Baez’s warrant for arrest until his condition improved.

The intricacies of the many factors in Baez’s case reveal an unsettling amount of uncertainty within the United States Bureau of Immigration. With the ever-changing legislation surrounding immigration policy, it becomes less surprising that Baez slipped into the country in such a chaotic atmosphere. An important consideration is that, while he did commit crimes and was subject to forced labor as punishment, his entry into the United States itself was not yet considered a criminal conviction, but rather a civil violation. Although Baez’s fate is left open-ended, reflecting on how his journey may have differed without his crimes or injury is critical to understanding the broader state of immigration at the time.

Document Analysis: Tensions Between Local and Federal Authorities

Inspector-in-Charge Brownlow often communicated with the Commissioner General of Immigration regarding Baez’s status, and following Baez’s initial injury, his condition progressively worsened. Brownlow was not immediately notified about this, but after he was informed, he wrote a detailed explanation to the Commissioner General about his suspicions: “with [Baez’s] condition having become critical, [local sheriffs] saw a chance to get rid of him and notified this office to come at once and take charge of him.” Brownlow’s statement highlights the urgency of the Monroeville sheriff after realizing Baez could no longer perform hard labor, and the sheriff’s eagerness to transfer Baez once he was no longer beneficial.

Brownlow further expressed his discontent to the Bureau by stating, “the Monroeville and Evergreen authorities being clearly responsible for his condition, should, in my opinion, bear all the expense in connection with his treatment.” Baez’s physician had previously stated that his condition would call for amputation and that the available resources were insufficient, therefore requiring more medical expenses. With the knowledge of how expensive Baez’s medical treatment would cost, Brownlow’s vehement suggestion that local law enforcement takes on the financial burden was meant as punishment. Local officers had caused the circumstances that led to Baez’s injury in the first place, and they were involved in the clear exploitation of his labor. Brownlow concludes his message stating that “there are no sailings out of Mobile whereby [Baez] could be deported,” indicating that Baez would have to be relocated to a port in Jacksonville or New Orleans, which would come from government funds. These details reveal that handling unauthorized immigrants included logistical difficulties and was not a straightforward process, and these bureaucratic strains only extended these issues.

Why It Matters

While Baez’s case file covers many different aspects of the immigration process, it primarily provides evidence towards historical abuses by law enforcement and the strained relationship between local and federal officials. Instead of getting Baez the necessary care or notifying the Bureau after Baez’s injury, the local sheriff attempted to transfer him to another jail without alerting the federal authorities. This revealed gross mistreatment by local officials, which is important because many undocumented immigrants continue to suffer similar abuses today. A recent case in New Jersey saw the conviction of an Immigrants and Customs Enforcement (ICE) deportation officer who was “accepting cash bribes and sex in exchange for providing employment authorization documents and concealing his employment of an undocumented immigrant.”

The difficult interactions between local law enforcement and federal officials have also continued to persist, especially in regard to the recent topic of sanctuary cities. Many politicians and local law officials in major cities, such as Seattle and Los Angeles, have announced their intent to limit cooperation with ICE concerning the enforcement of immigration laws. This sentiment stems from the belief that fear of deportation increases problems such as unreported crime and health issues, so these areas now prohibit questioning someone’s immigration status and refuse to detain some immigrants. However, the acting ICE Director, Thomas Homan, has called for “charging some of these politicians with crimes” for “harboring” undocumented immigrants. Evidently, corruption and tension within immigration law enforcement continues today, and Baez’s case reveals that these issues have existed for over a century.

Questions for Future Consideration

1) How can the relationship between local and federal law enforcement be improved today?

2) Did the system of convict labor affect the efficiency of immigration law enforcement?

3) What influence does an immigrant’s method of entry have on their quality of life?

Other Works Cited

“Former Deportation Officer Convicted of Accepting Bribes, Harboring an Undocumented Immigrant, and Lying to U.S. Immigration Authorities,” U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 10 Mar. 2017, https://www.ice.gov/news/releases/former-deportation-officer-convicted-accepting-bribes-harboring-undocumented-immigrant/.

Ramey, Sara. “It’s Not Local Law Enforcement’s Responsibility to do ICE’s Job.” The Hill, 10 Jan. 2018, http://thehill.com/opinion/immigration/368279-its-not-local-law-enforcements-responsibility-to-do-ices-job.

Shofner, Jerrell H. “Forced Labor in the Florida Forests 1880-1950.” Journals of Forest History, vol. 25, no.1, 2008, pp. 14-25.