By: Alyzette Consoli

Case File: 54833/96

Immigrant: Minnie Langford

On March 20, 1920, Minnie Bell Langford arrived in the U.S. through the port of entry in Vanceboro, Maine. A pregnant and single black woman, she had left her small hometown of Weymouth, Nova Scotia, Canada, to travel to New York City. Arriving in Maine, Langford did not have to face the same kinds of scrutiny that those coming in through Ellis Island did, although she still was subject to a medical examination and officials recorded her entering the country. The immigration station at Vanceboro was significantly smaller than Ellis Island, without the resources or ability to thoroughly examine all immigrants. Also, as temporary migration was often the expectation for those traveling across the U.S. and Canada border, policies restricting movement were enforced less stringently.

Only four days after arriving in New York, on March 24, 1920, Langford was admitted to Bellevue Hospital because she was “having pains” and worried that something may have gone wrong with her pregnancy. Once there, she was diagnosed with syphilis and kept for treatment. Langford’s stay in the facility rendered her a public charge, which was almost immediately brought to the attention of immigration officials.

Seward Wikoff, an inspector at the State Board of Charities, wrote a letter to the Acting Commissioner of Immigration at Ellis Island, P.A. Baker, informing him of Langford’s presence at the hospital. Promptly, on March 31, 1920, a warrant for Langford’s deportation was requested, and thus began the process of removing her from the country. This warrant was not served to Langford until October 31, while she was staying at City Hospital after being transferred there roughly six months earlier. At this point, her syphilis had been treated and her child was already four-months old.

An inspector from the Bureau of Immigration subjected Langford to an invasive, embarrassing interrogation that focused on her personal and sexual history rather than her financial situation or other circumstances. She was asked questions such as how long she had sexual relations with her child’s father and whether she had sexual relations with any other men. The inspector paid little attention to the $14 she had in her possession, the job skills she had attained working at a hospital, or the family members who could support her in New York. If Langford was being questioned as someone likely to become a public charge at her time of entry, why were her sexual encounters under scrutiny?

It was common practice at this time to exclude a woman on the basis of being “Likely to become a Public Charge” (LPC) when they were actually being targeted for moral turpitude offenses. It was simply easier for immigration officials to claim that someone was LPC rather than prove that they had committed acts of moral turpitude. Langford’s morality was primarily in question because of her pregnant and single state. This judgment was evident when the inspector took special care to assess how Langford became pregnant and how that pregnancy reflected her sexuality and morals. The venereal disease she contracted from the child’s father made her even more of a deviant in the eyes of the inspector.

Langford’s race also played a major part in how her ethics were assessed, as black women were often highly sexualized or assumed to be of “looser” morals. So, on December 7, 1920, Langford was deported on the legal basis that she had been “Likely to become a Public Charge” at the time of her entry. Officials used this as an easy catch-all to deport Langford and many others deemed to have committed moral turpitude.

If Langford returned to her hometown of Weymouth after her deportation, life may have been incredibly difficult for her. As a single mother in a small town, she would be judged for her relations out of wedlock. However, her file leaves it unclear as to what her actual plans were. It is unknown whether she may have tried her luck in a larger city, or if she even brought her child back to Canada with her.

Her Testimony

This summary includes the answers Langford gave while being interrogated by an immigration official. During this interrogation, the official asked Langford personal questions about her sexual history and other personal details. Especially without a lawyer present, this intense questioning in all likelihood made Langford anxious and fearful, as it did for many other immigrants.

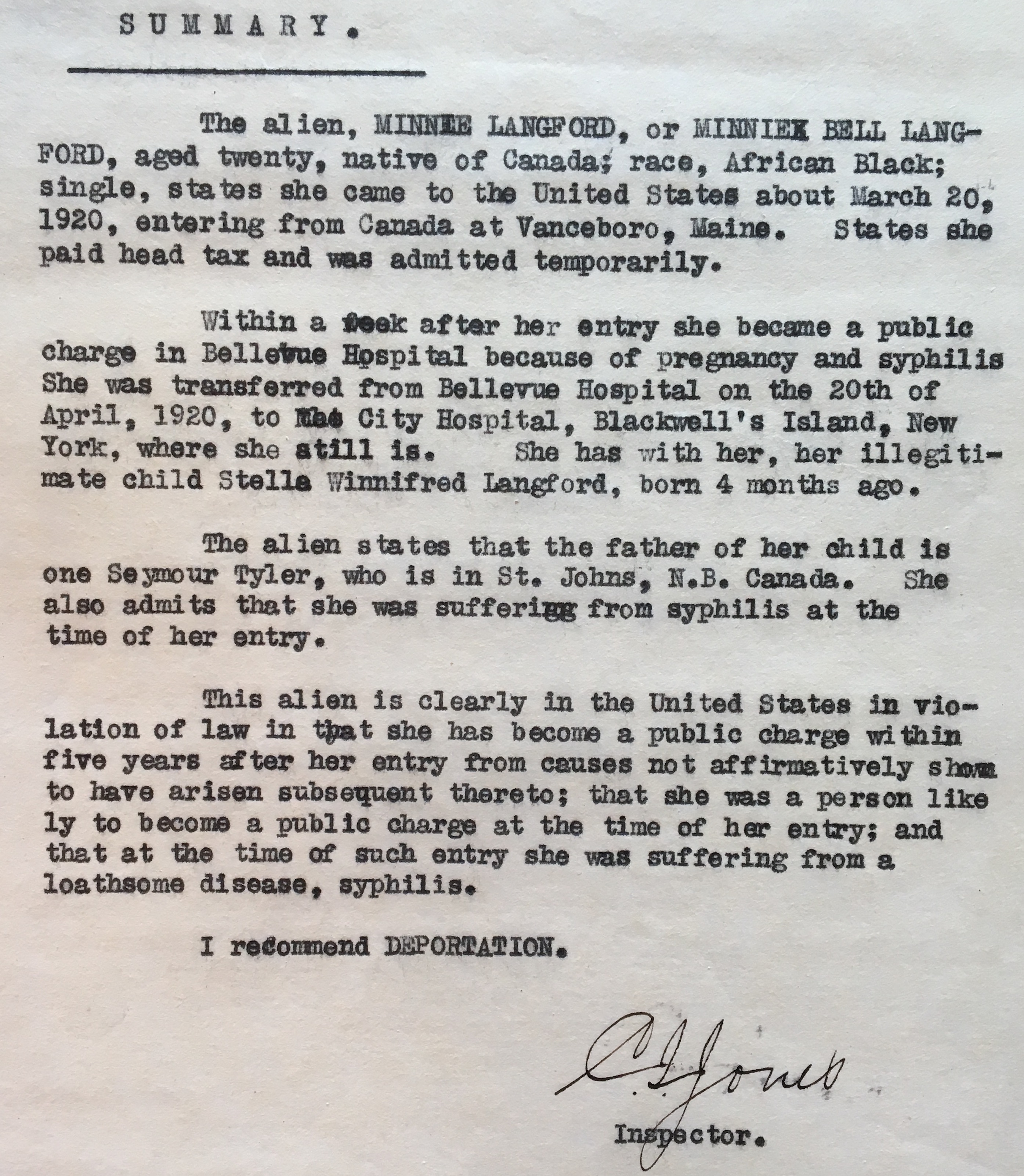

Langford’s case was summarized by the official in a terse, limited way, and the statements made by Inspector C.L. Jones mainly reflect the perception that immigration officials had of her, while omitting other information that was pertinent to her case. The inspector described only the basics of Langford’s story that made her deportable, and the summary report simply described her as a public charge who was suffering from syphilis. To present her as even more undesirable, the inspector used the word “illegitimate” to describe her child. This highlighted that her daughter, Stella, was born out of wedlock and cast judgment on Langford’s morality. However, the report leaves out the information she provided that would have benefited her, such as the fact that she had $14, a decent sum at that time, and family in the United States. She also mentioned in her testimony that she had worked in hospitals, so she had marketable job skills.

” This alien is clearly in the United States in violation of the law in that she has become a public charge within five years after her entry from causes not affirmatively shown to have arisen subsequent thereto; that she was a person likely to become a public charge at the time of her entry; and that at the time of such entry she was suffering from a loathsome disease, syphilis.”

In the final paragraph of the summary, the inspector does nothing but charge her with violations of the law. It is important to note that the inspector records her race as “African Black” within the first few lines. While it was common practice to record the race of every immigrant entering the country, Langford’s race was especially considered when deciding her fate. In the summary of a white woman’s case, there may have been arguments for her right to stay in the country. The $14, job skills, and family may have given any white woman the chance for redemption, but in Langford’s case, those facts were purposefully overlooked.

The Contemporary Policing of Women’s Bodies

Minnie Langford’s case brings into question issues surrounding the regulation of women’s bodies and the racialization of sexuality. Langford, like many women of her time, was interrogated and scrutinized for her pregnancy and sexual history. As a black woman, she was presented in an even harsher light and her child was deemed illegitimate. In today’s immigration debate, there is similar rhetoric surrounding immigrant women, as politicians discuss terms such as “anchor babies”. Just like in 1920, women are being policed by discussions that question the morality of the use of their own bodies and their sexual agency.

These discussions are further embedded within issues of race. Langford and her child’s legitimacy as potential citizens were denounced because of their African heritage. In the same way, Mexican women, usually considered nonwhite, are often rendered as villains, coming to the U.S. with an agenda, and their children are considered lesser citizens.

Langford’s case also addresses how nonwhite women are made to be the sole actor in their sexual history. Never in Langford’s case did officials perceive the father of her child to be at fault or responsible for her pregnancy. It is solely the woman’s choices and morality under scrutiny. Even now, women fleeing sexual and domestic violence who may be pregnant are often not seen as victims by the state and anti-immigrant advocates. Instead, they are portrayed as having nefarious morals and intentions, and often are assumed to be lying about the danger they may have faced in their origin countries in order to achieve their agenda.

Questions for Future Consideration

1) How do immigration policies and conversations reinforce patriarchal values and systems?

2) How is it that policies with neutral language about race are enforced with a racial bias?

3) How are the bodies of white women and women of color policed differently?