By: Sarah Hartranft

Case file: 53475/345

Immigrants: Alice Bromilow and Frank Atherton

The year is 1912. An English widow hopped aboard a ship with her grandson with the hope of being reunited with her family in a place she knew once before: the United States. Her name was Alice Bromilow and she was ready to be reunited with her children in the United States. Bromilow had previously resided in the United States with her husband, who was a naturalized citizen. However, the two had later returned to England where Mr. Bromilow eventually passed away. Back then, a woman’s citizenship could be determined by her spouse, therefore Mrs. Bromilow lost her American citizenship after her husband’s death.

During her time in England, Mrs. Bromilow’s son-in-law also passed away, and she assumed care of her daughter’s third child, Frank Atherton. When they arrived in the United States, Atherton was debarred because he was unaccompanied by a parent, and Bromilow was debarred because she was deemed “Likely to become a Public Charge” (LPC). The LPC clause was created to broaden the spectrum of who could be considered unfit to enter the country. But in cases such as Bromilow’s, the issues were a bit deeper than the surface.

When Bromilow arrived in the United States, she reached out to her son, who had been in the United States but had recently become unemployed. She also reached out to her brother-in-law, who was reluctant to become involved in her case. Bromilow’s brother-in-law failed to pay for the first telegram immigration officials sent to him, inquiring about his willingness to support Bromilow, and failed to answer a second attempt to contact him as well. As a result, his financial situation was unknown but assumed to be ill-suited to support Bromilow and Atherton. None of these interactions with her family were sufficient to convince immigration officials that she should be allowed to enter the United States, so the immigration officials investigated her life a little more.

Bromilow was 57 at the time of her arrival, and in England, she worked as a paid housekeeper. Alice Bromilow was not useless and she proved to be able to support herself in England, but that was not enough for the immigration officers. Since they assumed she was too old to remarry, they concluded that she could not take care of herself because of the societal idea that a man needed to support a woman. Women were still considered to be the property of men and fully dependent on a husband through the institution of marriage.

In fact, in 1907, Congress passed a provision that declared “any American woman who marries a foreigner shall take the nationality of her husband.” This made it clear that a woman’s allegiance was owed to her husband, and not her nation, reinforcing the notion that women were considered second-class citizens. Citizenship was never permanent for women, and its strength depended on many components. Mr. and Mrs. Bromilow were American citizens for 14 years, but when they went back to England and Mr. Bromilow passed, Mrs. Bromilow automatically lost her citizenship.

Two Sides of the Story

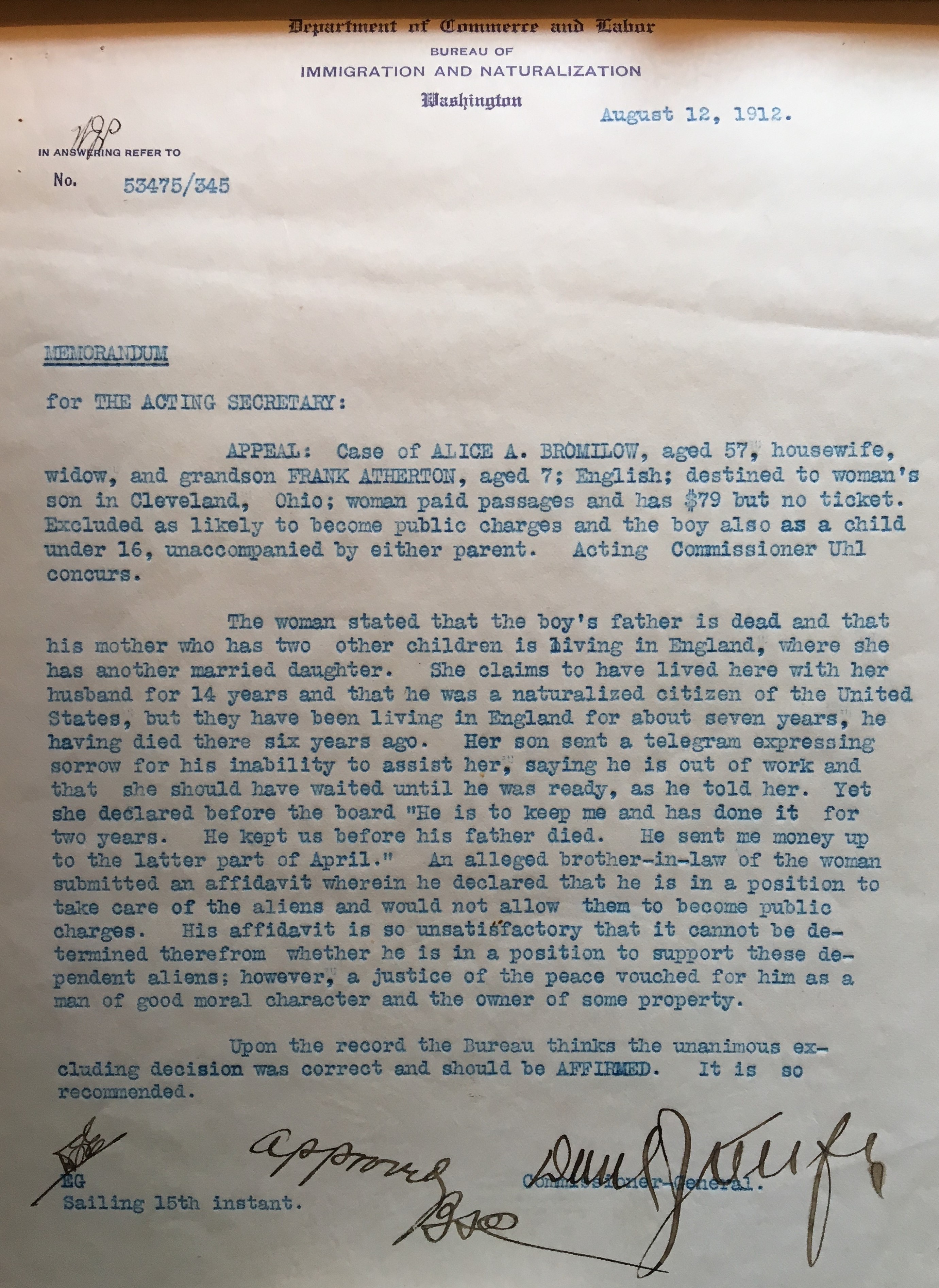

The following document is a memorandum from the Commissioner General of Immigration to the Acting Secretary of Labor. The Commissioner General is explaining his agreement with the officials at Ellis Island to deny entry to Bromilow and Atherton. Atherton’s role in this case was not as controversial as Bromilow because he was debarred on very technical terms: he was not accompanied by either parent, therefore he could not come into the country (it was also inferred that Bromilow was not Atherton’s legal guardian).

In her interrogation, Bromilow was fearful of returning to England where there was no one to support her and her grandson. Since her son was soon to get another job, she knew the United States was her better option. Bromilow’s son was revealed to have sent a telegram saying that she should have waited until he had a job again to come over, to which she replied: “He is to keep me and has done it before.” The Commissioner General used Bromilow’s continuous advocacy for her son’s stability to make her seem stubborn and illogical.

The Commissioner General eventually confirmed the opinion that Bromilow was likely to become a public charge, even though he was sending a widowed grandmother back to England where she had no one. Ultimately, after a one-sided account of Bromilow’s story, the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization affirmed the unanimous decision to exclude Bromilow from the country.

Why It Matters

Being an immigrant is never easy, but neither was being a woman in 1912. Alice Bromilow happened to be both. In this era, women were considered second-class citizens. Often, women were expected to raise children and be reliable housewives. These expectations limited unmarried, widowed, and older women. Since Bromilow was 57, she had already bore children and spent her life as a housewife, and since her husband passed, she would have liked nothing more than to return to the United States to be with her adult children. However, because she was older, immigration saw no need for her in the U.S. They assumed she was too old to marry and she would not be able to support herself, so they deemed her likely to become a public charge.

Women having second-class citizenship is an ancient idea that found its way to American society and caused Bromilow to be debarred. American government strongly enforced this notion in cases like Bromilow’s. They often debarred women that were unaccompanied by men due to the idea that if they had no man to take care of them, their morals were in question.

ADDITIONAL Works Cited

Cott, Nancy F. 1998. “Marriage and Women’s Citizenship in the United States, 1830-1934.” American Historical Review, vol. 103, no. 5, pp. 1440-1474.